Filioque clause: Difference between revisions

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

=== The Filioque makes a difference === | === The Filioque makes a difference === | ||

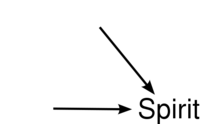

Without the Filioque clause, the Father would have twins and there would be no way for us to appreciate the difference in the Father's relationship to the Son and to the Spirit. Both the Son and the Spirit would be ''from'' the Father; their relationship to each other would be unspecified and there really would be no way to tell them apart from each other--they would differ in name only. | |||

File:Without filioque.svg | |||

== Links == | == Links == | ||

Revision as of 01:17, 27 August 2010

"Filioque" is two Latin words run together. "Filio" is the ablative case of "filius," which means "son." "Que" tacked onto the end of a word is one of the ways Latin has for saying "and." So the literal translation of the word is "and the Son."

The phrase appears in the version of the Nicene Creed used in the Roman Catholic Church and many other western Christian denominations. The full Latin sentence in which it appears is:

"Et in SpÃritum Sanctum, Dóminum et vivificántem: Qui ex Patre Filióque procédit."

"... and in the Holy Spirit, Lord and Giver of Life, Who proceeds from the Father and the Son."

This phrase does not appear in the original version of the Nicene Creed, which was composed in Greek by the Council of Nicea in 325 AD (Nicea is in Greek territory, near Constantinople) and revised by the Council of Constantinople (381 AD; also a Greek council held near Constantinople).

Catechism of the Catholic Church

246 The Latin tradition of the Creed confesses that the Spirit "proceeds from the Father and the Son (filioque)". The Council of Florence in 1438 explains: "The Holy Spirit is eternally from Father and Son; He has his nature and subsistence at once (simul) from the Father and the Son. He proceeds eternally from both as from one principle and through one spiration. . . . And, since the Father has through generation given to the only-begotten Son everything that belongs to the Father, except being Father, the Son has also eternally from the Father, from whom he is eternally born, that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Son."

247 The affirmation of the filioque does not appear in the Creed confessed in 381 at Constantinople. But Pope St. Leo I, following an ancient Latin and Alexandrian tradition, had already confessed it dogmatically in 447, even before Rome, in 451 at the Council of Chalcedon, came to recognize and receive the Symbol of 381. The use of this formula in the Creed was gradually admitted into the Latin liturgy (between the eighth and eleventh centuries). The introduction of the filioque into the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed by the Latin liturgy constitutes moreover, even today, a point of disagreement with the Orthodox Churches.

248 At the outset the Eastern tradition expresses the Father's character as first origin of the Spirit. By confessing the Spirit as he "who proceeds from the Father", it affirms that he comes from the Father through the Son. The Western tradition expresses first the consubstantial communion between Father and Son, by saying that the Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son (filioque). It says this, "legitimately and with good reason", for the eternal order of the divine persons in their consubstantial communion implies that the Father, as "the principle without principle", is the first origin of the Spirit, but also that as Father of the only Son, he is, with the Son, the single principle from which the Holy Spirit proceeds. This legitimate complementarity, provided it does not become rigid, does not affect the identity of faith in the reality of the same mystery confessed.

Scriptural Evidence

(To be developed ...) Jesus sometimes talks about the Father sending the Spirit and at other times says He Himself will send the Spirit.

Appreciating the Dogma

If the dogma is false, none of the following reflections can establish its truth.

If it is true, then I hope that the following reflections will shed some light on what it reveals to us.

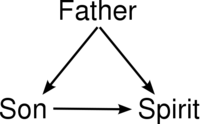

If we use arrows to indicate Who is from Whom in the creed, we get the following diagram of the relations between the Persons of the Trinity:

We may focus on each Person individually and see something about the character of that Person.

The Father alone has no father

The Father is the fatherless origin of all other persons, whether uncreated (the Son and the Spirit) or created (angels, humans, and any other extra-terrestrials, if they exist). He is from no other person; all other persons are from Him. If we associate masculinity with giving and femininity with receiving, then the Father has a purely masculine character.

The Son receives from the Father and gives to the Spirit

The Son--like us--has both masculine and feminine qualities. He receives Himself from the Father and gives Himself to the Spirit.

The Spirit is pure receptivity

The Spirit receives Himself from the Father and from the Son. In this sense, the Spirit has a purely feminine character.

- Why do we call the Spirit 'He' if He apparently has a purely feminine character?

- Masculinity and femininity do not cancel each other out.

- As the Spirit of the Father, the Spirit is properly called "He" even though what distinguishes Him from the Father and the Son is receiving Himself from them.

The Spirit is the love between the Father and the Son

The Spirit is a Person-between-Persons. He is the Spirit of the Father as well as the Spirit of the Son. We may think of Him as the love between the Father and the Son.

The Filioque makes a difference

Without the Filioque clause, the Father would have twins and there would be no way for us to appreciate the difference in the Father's relationship to the Son and to the Spirit. Both the Son and the Spirit would be from the Father; their relationship to each other would be unspecified and there really would be no way to tell them apart from each other--they would differ in name only.

File:Without filioque.svg